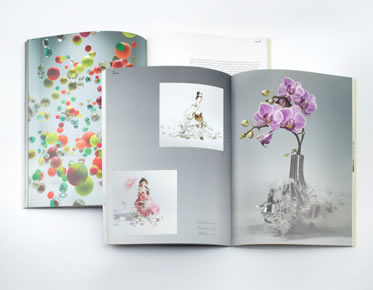

NYTM Split Cover

Photographs for The New York Times Magazine

12.10.2008

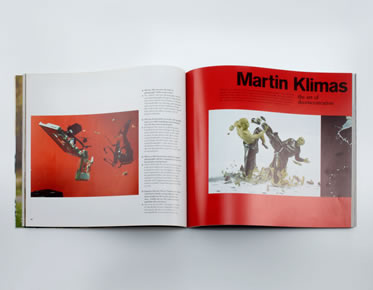

If your Sundays, like ours, involve acquiring an armful of newsprint in the form of The New York Times, be extra vigilant as you choose your copy today. Book Review? Check. Week in Review? Check. Magazine? Not so fast. This week's New York Times Magazine is The Food Issue, and the editors had such an appetite for the exploding produce photos of Martin Klimas that they couldn't choose just one for the cover. So they chose three, randomly trisecting the magazine's press run to include a trio of covers that feature an exploding ear of corn, an apple, or a pumpkin (we got the corn but would have preferred the pumpkin). As for how the German photographer achieves the explosive effects, it involves firing a "projectile" into the unsuspecting fruit or vegetable rather than fancy Photoshopping, notes the magazine, adding that Klimas "is somewhat guarded about his technique." It all gives new meaning to the term photo shoot.

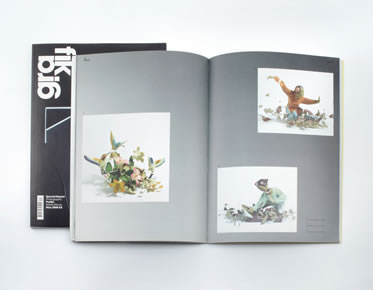

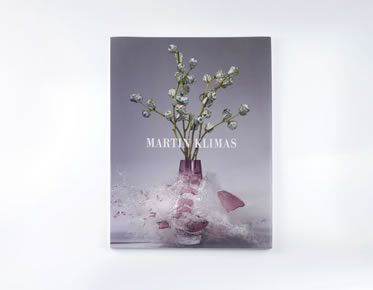

Exhibition Catalogue

Solo Show COSAR HMT

January 2008

ISBN: 978-3-89355-964-0

When Still Lifes Burst Apart Like Dreams

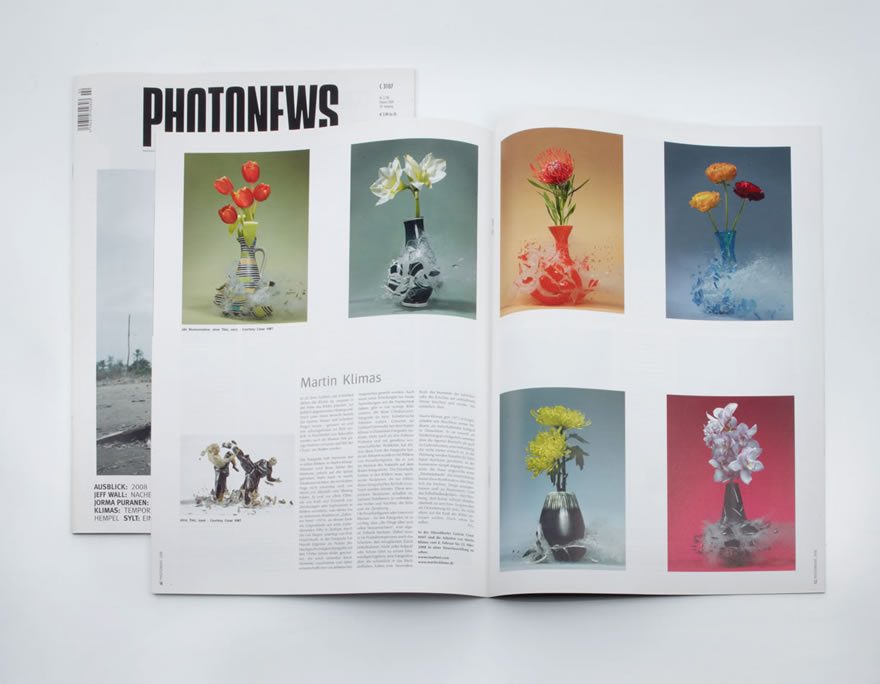

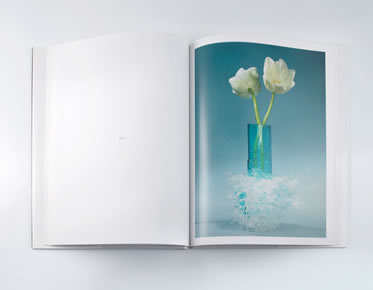

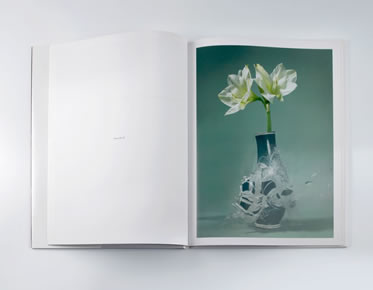

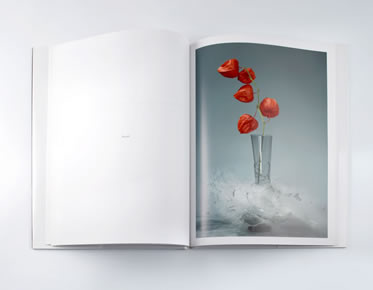

The florist’s bouquet is once again gaining in popularity as a token a guest offers his host, whether friend or relation. Very quickly a suitable vase is sought among the selection of colored or transparent, rotund or angular ones at hand. Suddenly the vase explodes. Is it a calculated shock or a plain and simple provocation when Martin Klimas blows our bourgeois conventions to pieces?

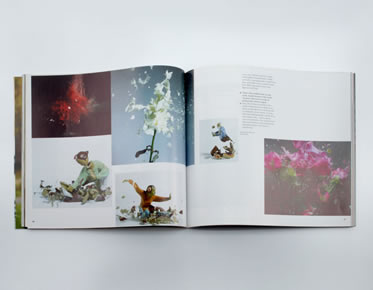

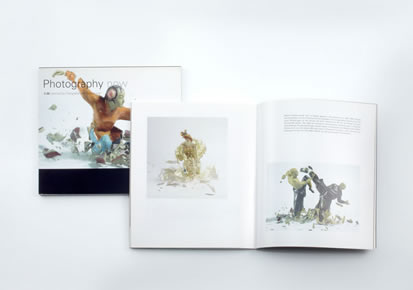

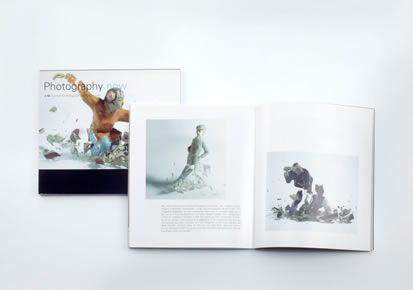

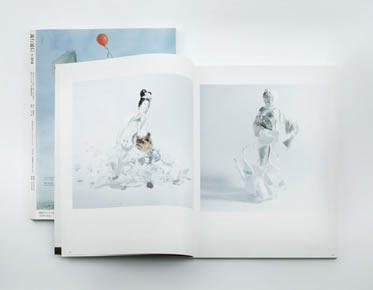

The main object in his pictures is an arrangement of flowers in a vase: tulips or carnations, orchids or amaryllis. These are placed squarely at the picture’s center against a neutral, mostly monochrome background; no other detail distracts the attention of the viewer. It all reminds us of classical studio and product photography, something Klimas is very well acquainted with. Then with a spring-powered firing device, the Düsseldorf photographer himself aims at the vase, which thus bursts into a thousand pieces. Klimas makes just one photo, set off by the noise the projectile makes on impact. In the next fraction of a second, the flowers – without the support of the vase – will be thrown sideways or tumble to the ground, but this is a sight the photographer spares us.

It is a simple test set-up that at first glance suits a physics laboratory more than it does a photo studio. But with the help of high-speed exposure, we can see things in a way that is not possible for the human eye alone. Even if we were capable of viewing the entire course of the destruction with our own eyes, we would not subsequently be able to break up the scene so as to register it. Here in the photograph, the visual experience is frozen into a single instant, an in-between state in which standstill and explosion exist dynamically alongside each other. The dualist fragmentation takes place horizontally, mostly in the bottom third of the picture: idyll above, catastrophe below. Occasionally the, in part, exotic form of the flower oddly paraphrases the way the vase destructs. The glass vases shatter into countless particles, while the ceramic or stoneware vases only separate into large shards; in any case the receptacle – directly after impact with the destructive projectile – appears to sink to its knees.

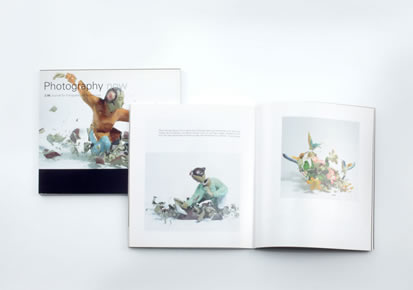

At the same time, with this series entitled “Temporary Sculptures”, the photographer only anticipates the fate that awaits all earthly things and will eventually befall them: destruction or decomposition. Klimas makes the vases explode – and does so for one single photo; it is, in fact, a seemingly absurd idea to take something intact and break it up into its components and document the decisive moment. Via the compression of the explosion in a visual fraction of a second, something new comes about (along with the questioning of idyllic illusion), which corresponds to the photographer’s intention: he releases the objects from their functional purpose and very precisely documents this turnabout. What emerges is a quite unique link between beauty and perishability, between the static and dynamic, between the successive and the simultaneous – and all within a single image.

Whichever. The aggressive gesture of conscious destruction is unsettling. However, Klimas succeeds in aestheticizing and re-evaluating this process so that the traditional, art-historical concepts of the still life, i.e., vanitas, is in fact expanded, if not to say exploded. He not only shatters vases, but also established topoi such as dreams. Klimas makes use of dematerialization as a prerequisite for the metamorphosis of the form. We could call him a sculptor with a camera who, in 5000th of a second, creates a new form out of an existing one.

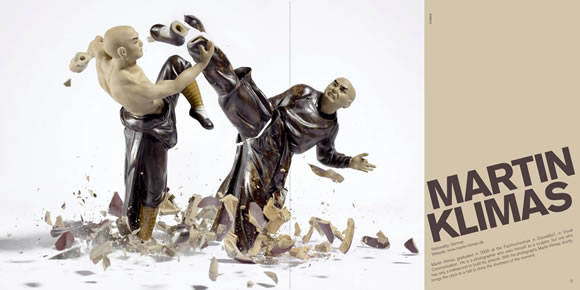

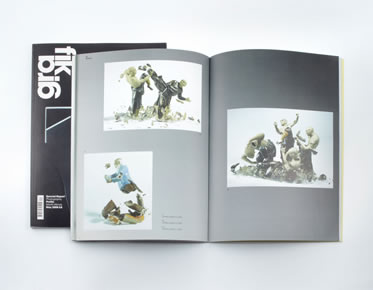

It is quite unusual today that a photographer born in 1971 should choose to work on such a complex visual theme with analog image technology that forswears any subsequent digital manipulation. This also applies to Klima’s earlier projects when he quite simply let small ceramic figurines fall to the ground. In just this way, pink-robed ladies or Asian kung-fu martial artists disintegrated into fragments solely so that Klimas could visualize the moment of impact. Curiously enough, the fighters with their hand techniques seemed themselves to break into pieces. With these sculptures – more than with the bursting vases – the disintegration of the form, the insight into the material properties beyond its outer contours is made evident. Klimas, both playfully and complexly, describes the essence of the form as that of transience.

The systematics behind his very original as well as unique series of photos multiplies the basic pictorial concept. Klimas always parses the flower-vase-color combinations with the same frontal view and neutral lighting with no cast shadows. In several photos there is, at least at the center of the picture, a third level that subtly mediates between the opposing forces and visually prepares the way for the other area in question, such as a hairline fissure in the vase’s glass or ceramic exterior that announces its imminent functional extinction. Yet the particularity here is that this takes place not successively, but simultaneously. And the delicacy of the fissure intensifies the brutality of the destructive gesture.

A photo directly before the shot, i.e., of the flower still-life alone, would be photographically just as uninteresting as one that showed the aftermath of the final fragmentation, when flowers and vase shards have fallen to the ground. And within a sequence of the entire event – that is, inclusive of all the aesthetic, in-between stages – viewers would surely decide on the same shot that Klimas favors. However, the photographer does not choose from different variations of the nearly same situation, but accepts the single take as the final image only when the tension between the static and the dynamic is to him in sync. Chance, too, helps bring about the production of the photo.

The photographic strategy here was schooled along the lines of the experimental photographer, Harold Edgerton, and the amazing effect he achieved with stroboscopic bursts of light and high-speed camera shutters that, already in the 1930s, froze breakneck-speed actions onto a negative, such as that of a bullet in flight.

Beyond “Doc” Edgerton, Klimas also names Eadweard Muybridge as an important inspiration. By means of the test set-ups he designed in the 1870s, Muybridge was able to prove that horses lifted all four hooves in the air when galloping, a question hotly debated in artists’ circles at the time. At that time, it could neither be verified nor negated by the naked eye; thus photography came to be used as a technical expedient. Muybridge’ series of photos published in the 1880s under the title “Animal Locomotion” changed our idea and perception of the sequence of animal and human movement.

Also Naoya Hatakeyama – because of the formal as well as thematic parallels – should not go unmentioned here. For some years now, this photographer in his native Japan has ventured with his remote-controlled camera very close to quarry explosions and recorded the way stone chunks fly towards the camera and seemingly also towards the viewer. Via the choice of photographic technology in these exploding landscapes, the time depicted seems to come to a standstill in a way similar to Klimas’ radical and elemental still lifes.

Matthias Harder

From the German

by Jeanne Haunschild